The Sentinel #18

In this post, I want to begin analyzing SEA (South East Asia), starting with Vietnam. While we are here, it is a tragedy that South East Asian countries are often boxed in together in one category. They are proud and distinct countries with rich political histories, and in fact, many regions within countries with their heritage, languages, faiths, and livelihoods — a region arguably more diverse than Europe.

Many cultural and geopolitical observations about Vietnam are through the lens of the US-Vietnam War. While they offer some important lessons, I hope to take a different perspective in examining Vietnam’s role in supply chains.

There has been a slow but sure trend of manufacturing shifting out of China over the past few years, as a part of a secular trend that pre-existed the current global tensions and pandemic shifts in policy. Sometimes these glacial shifts don’t register in our consciousness until a massive shift has been suddenly noticed. The increasing geopolitical tensions between China and the US, and new industrial policy in the US have accelerated the trend.

In the past few posts, I have been talking about the intended shift from manufacturing locations to places like India. Manufacturing Scale in India is still in its infancy.

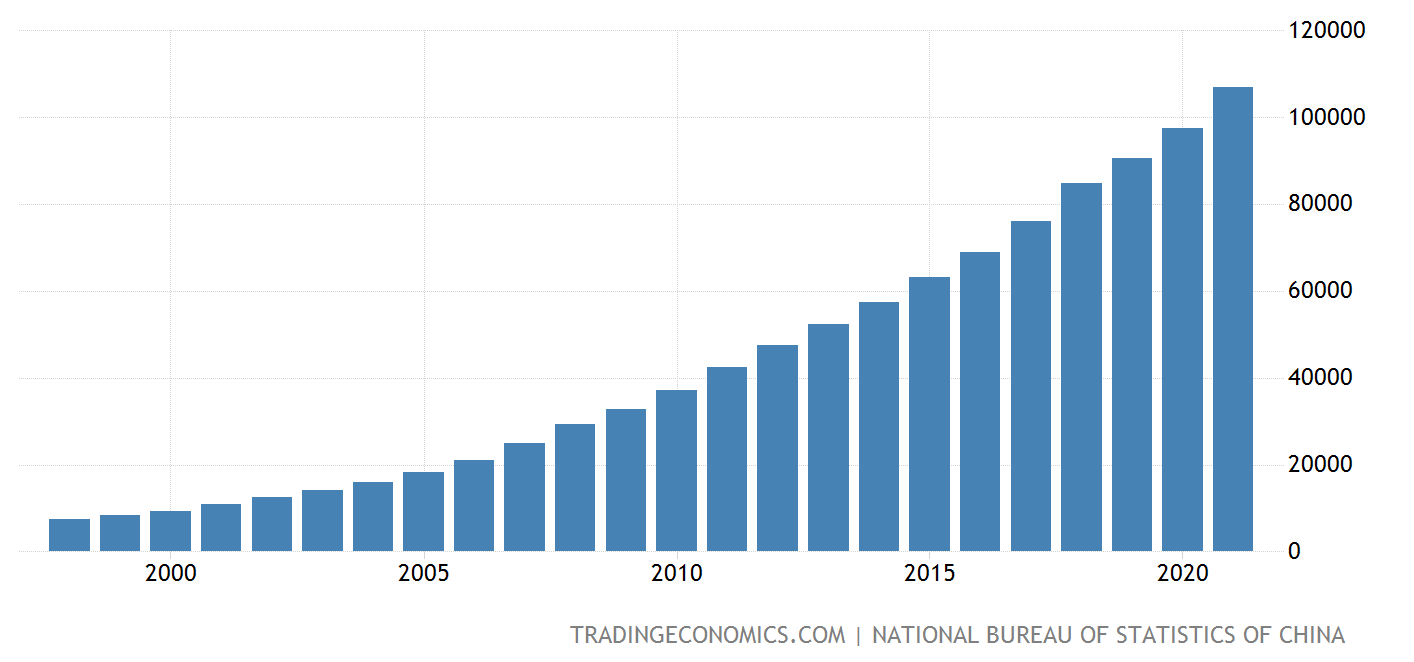

Wage Growth in China

It helps to examine how this capacity shift is necessitated by a trend over a long period. Here is the data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China that I often show in my Operations class.

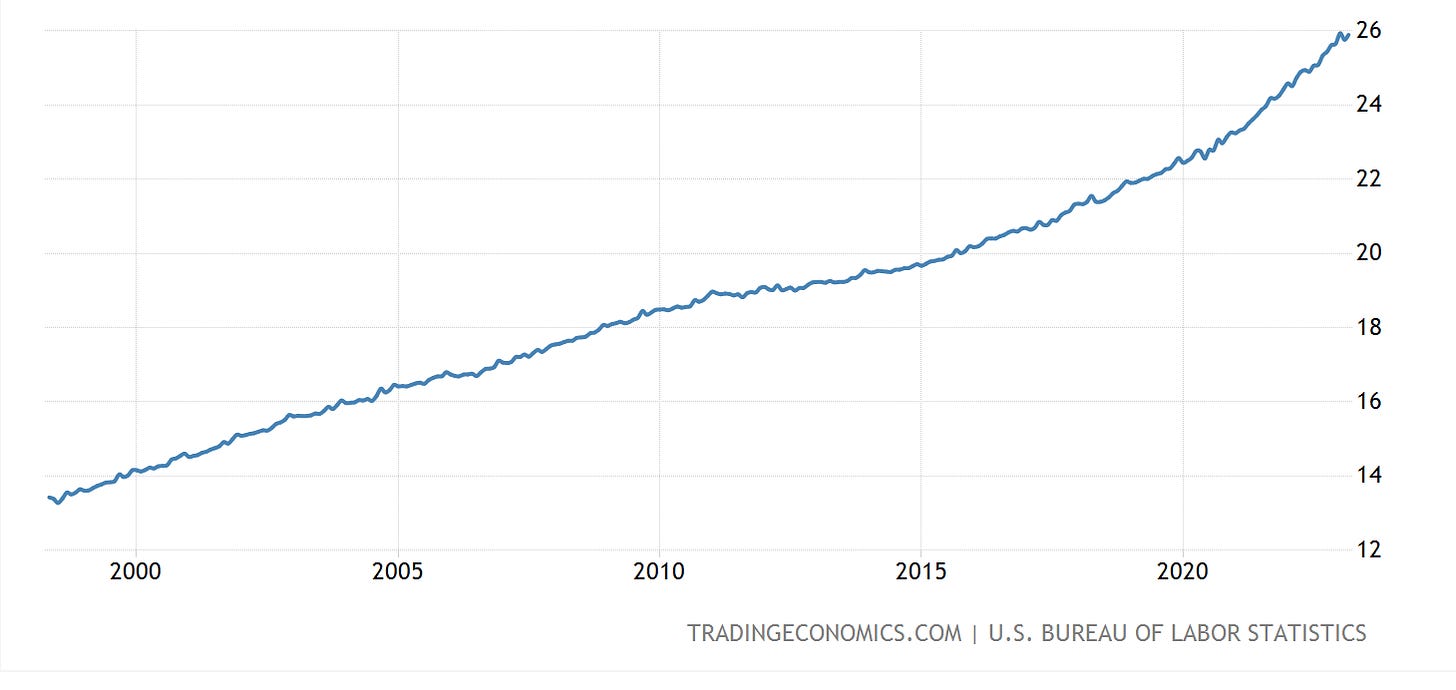

Manufacturing wages now are substantial in China. Looking at growth (2010-2020), wages are nearly three times more than the wages a decade ago. Compare this growth to US manufacturing wages which have grown by at most 35% (going from ~$19 to $26) over the same period when wages in China tripled.

As both charts clearly show, manufacturing wages in China have been growing faster than in the US and at a continued pace. Given the high point at which the wage differential began in the 1990s, the wage difference between US and China manufacturing will persist for a while.

To understand why this is the case, we have to look at a few demographic explanations. First, China has a supply constraint, because it got older, very quickly and a younger workforce is not available for manufacturing.

In my Apple in India post, I compared the median age of the population in India with that of China. India is still a very young country — by which I mean the median population is young — whereas China has grown older mainly due to the one-child policy intervention. A great book that examines the cultural and social impact of the policy is One Child: The Story of China’s Most Radical Experiment by Mei Fong, which I mentioned in my very first post on Supply Chains and China. Even though the policy has been now reversed and relaxed, the social preference of having only one child is continuing in China.

This supply crunch can be further seen through the lens of the growth in high school graduation rates in China. Only a third of the Chinese population graduated high school as late as 1990. Now, it is about 80% (getting closer to the US average which is at 85%). (Also, note that this young population is diminishing).

If you are the only child in the family born in the late 90s in China, and graduating from high school or college in China in the new century, your ambitions don’t end at merely moving to urban areas in the coastal regions (or working in a factory). A child, the apple of the eye, supported by two parents and maybe even the only grandchild of four grandparents: The ambition expands to founding your own company — a hardware or software business.

So where will then the manufacturers find the younger workers? Not in the cities, where millions have entered the vast middle class.

It changes the manufacturing calculus of where to make products.

So, I suppose one goes inland — from the eye (Beijing) and the chest (Shanghai) of “the rooster”, into its innards — lengthening the supply chain and frankly, problems.

The other option is to look out for some neighborly help in South East Asia. The wages in China exceed the manufacturing wages in adjoining South East Asian countries.

Nevertheless, shifting scaled manufacturing has specific problems. Disruptions are costly. Sometimes there are accidental nudges like the chaos of the pandemic. In the landscape of rising wages, the extended lockdown situation in Shanghai was a proverbial “straw” on the camel’s back.

Onshoring? Not yet… So, Friendshoring?

A firm cannot just shift its manufacturing plant and start production at scale. Some of the learning is fast and transferable, such as in Apparel manufacturing, which happens at an accelerated pace and persists for a longer period, as there is quite a bit of transfer learning that happens between products.

Not so with electronic devices. Learning by doing proceeds slowly, and there is a significant process of learning for every new product. A factory can’t just start manufacturing Macbooks because they have been making iPhones.

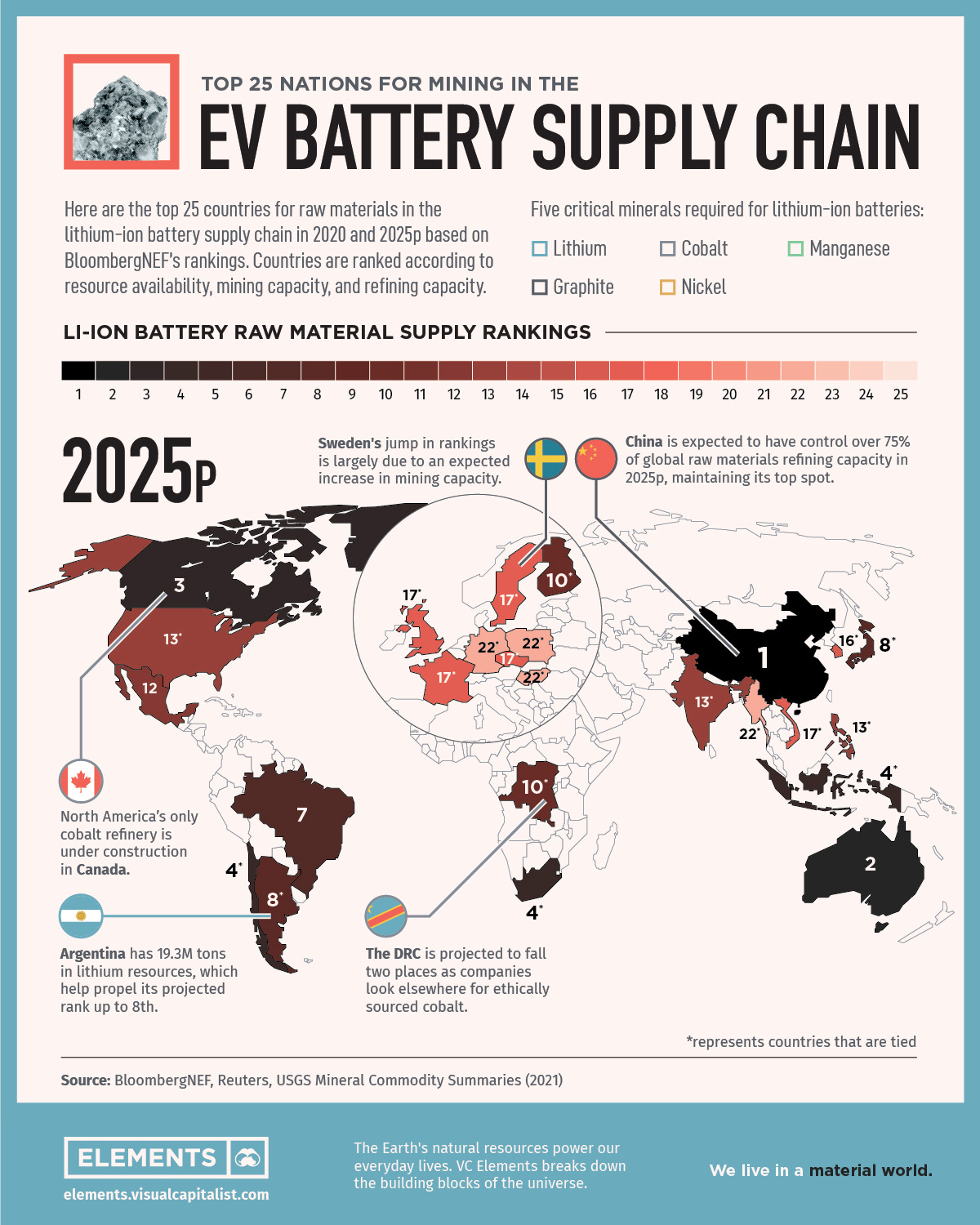

Almost all supply chains have become many-tiered, from source material to final product, and the tiers are spread across countries and across continents. The more you do end-to-end analysis, from the raw material level to the last mile to the customer, the more globally spread the supply chain becomes.

The global nature of raw materials can be seen in the mining extraction for battery supply chains, in the picture above. In the case of electronics, one deals with large component manufacturers (Intel, TSMC) and suppliers, and even equipment manufacturers (like ASML) that are in many varied countries. By moving the manufacturing away to another location, a firm is very likely complicating the supply chain “map”.

So it is important to have friendly relationships with neighbors. One can’t just ‘friend shore’ all of a sudden, like using the ‘phone a friend’ lifeline when you want to win a million dollars on the TV Show “Who Wants to be a Millionaire?”.

Why Vietnam?

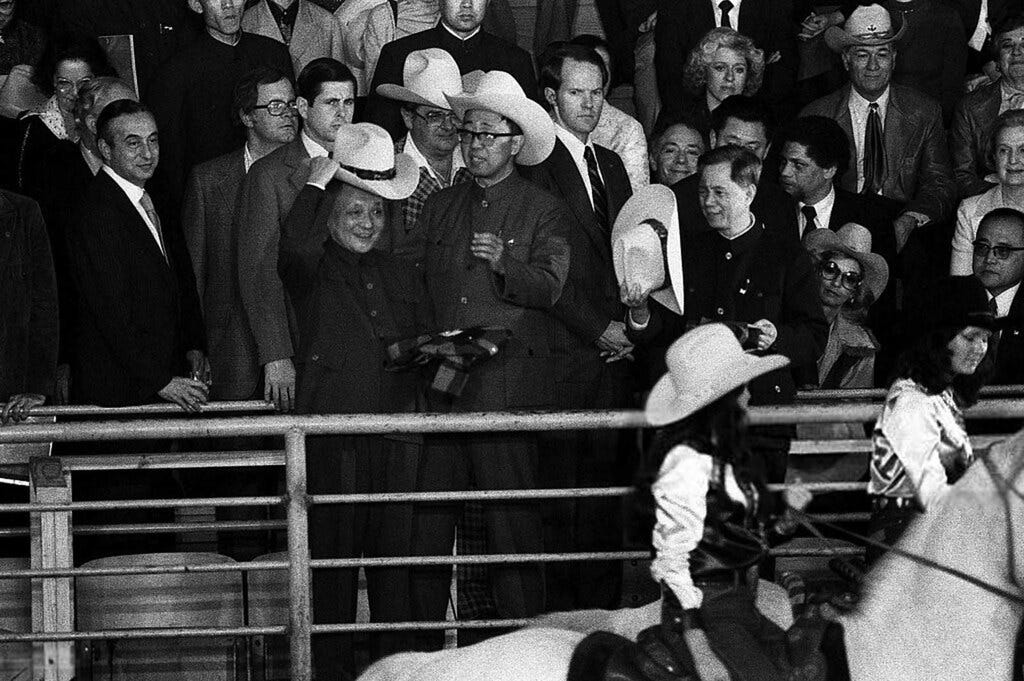

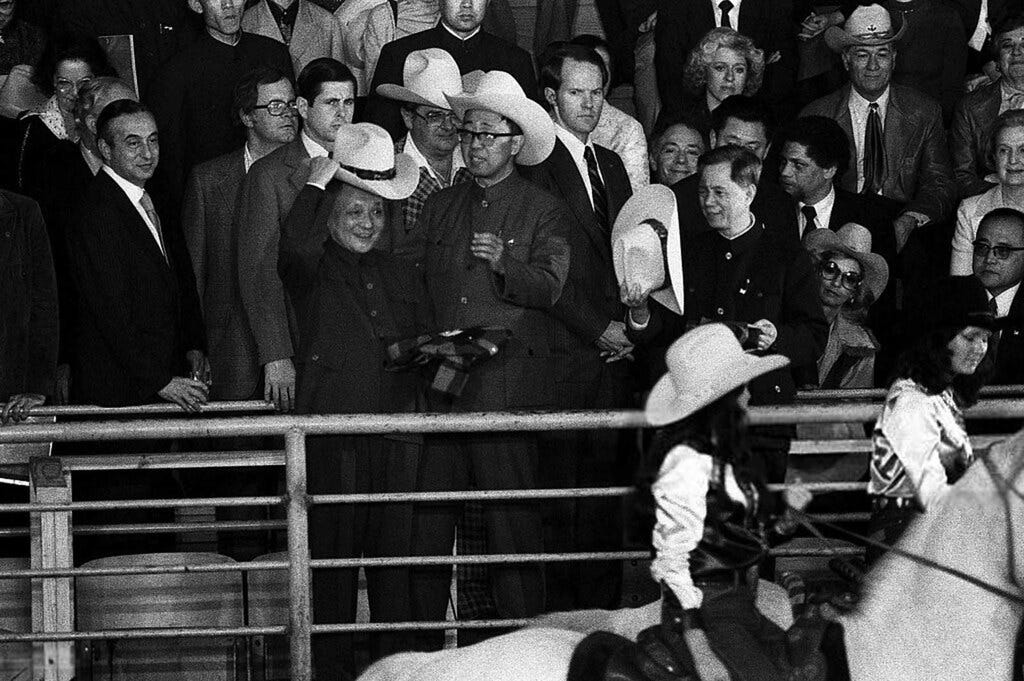

The Sino-Vietnamese relationship shares the same nature of the relationship as the Sino-Indian one: wary coldness. The battles are fresher in memories than the Indian engagements. In 1979, the same year Deng Xiaoping visited the US, met President Carter, traveled to the Kennedy Center of Performing Arts (starring John Denver and Harlem Globetrotters), Houston Space Center, and also met executives at Coca-Cola in Atlanta and Boeing in Everett, WA, the People’s Liberation Army troops led an incursion into the Northern Part of Vietnam.

Here is the historian JD Spence, in The Search for Modern China (pg: 593)

The Chinese claimed that their intervention was a response to a series of border provocations, and a protest against Vietnam’s actions in Cambodia and the country’s friendship towards the Soviet Union. One can also see another motive for the Chinese display of force. At a time when domestic economic expansion was given so much prominence, the Chinese leaders were determined to show that in their force of agricultural reform, technical training, and industrial development […] they were not neglecting the fourth modernization: national defense.

In 2023, one might observe that the relationship dynamics now are trending in directions exactly opposite to that of 1979 — when the US-China relationship was thawing, and the China-Vietnam interaction was at its nadir. The US-China relationship now is definitely not warm. And, China depends on Vietnam’s supply chain capabilities perhaps more than ever.

So, all of this puts pressure on Supply Chain Coordination. It is in the interest of the manufacturers in China (and the Apples of America) to encourage contractual and positive relationships with Vietnam. There are comparable advantages that Vietnam offers over other SEA countries.

For current supply chains, majorly positioned in China, Vietnam is attractive on many fronts.

- The special economic zones in Vietnam are close to China both geographically and economically facilitating the movement of goods and supply chain collaboration. Vietnam has a long coastline of 3260 km! (btw: Did you know about the Coastline paradox that Benoit Mandelbrot worked on?, footnote). The ports are developed, and there is reliable power and widespread internet access. Perhaps, most critically, Vietnam shares a land border with China and is also the closest SE Asian country to the manufacturing hubs in Guangdong province.

- The wages in Vietnam are cheaper than the other ASEAN countries (Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and the Philippines). They are also not growing as fast as wages in China, which implies that the comparative wage advantage may continue for a while.

Shifting Capacities from China to SE Asia is still fraught.

The shifting of capacities faces many hiccups – both cultural and political. Recently, there were news reports that some of the manufacturing companies and suppliers were racing to exit China, including news that Apple’s suppliers in China will shift out capacity faster than anticipated, to preempt fallout from escalating Beijing-Washington tensions.

AirPods maker Goer Tec Inc. is one of the many manufacturers exploring locations beyond its native China, which today cranks out the bulk of the world’s gadgets from iPhones to PlayStations. It’s investing an initial $280 million in a new Vietnam plant while considering an India expansion, Deputy Chairman Kazuyoshi Yoshinaga said in an interview.

Something curious happened after that particular news announcement. Bloomberg reported that Deputy Chairman Kazuyoshi Yoshinaga is departing for “personal reasons”. No more elaborations.

Fortunately, academic freedom allows me to comment on this issue. There are two observations we can deduce: One, Apple really really likes to keep their suppliers’ communications tight. Two, the shift of manufacturing capacities that is happening from China to Vietnam is indeed real.

It is a significant shift in capacity, given that Apple made more than 50m iPads in China, but the shift perhaps feels even more significant in our consciousness. For iPad manufacturing, the observation is certainly true, that many of the suppliers are still located in China.

—

Yet, as I often like to say, there is a center of gravity to the map of “know-how”.

Even though manufacturing is ostensibly shifting outside of China, the know-how is sticking within the traditional supply chain. Chinese contract firms like BYD that set up Apple’s assembly lines in China are the same ones setting up their assembly in Vietnam.

One way to understand which products Apple has chosen to move to Vietnam depends on the maturity of the product, and whether the production process has scaled and matured. For instance, even though Apple now produces a significant amount of Airpods in Vietnam, there are always hiccups. When it came to the development and production of the new generation Airpod 3, the production shifted to China. The “reverse shift” happened signifies the need for product development talent.

“New product introductions,” require companies and suppliers to work together to produce a feasible design, then the product, and the process for manufacturing and decisions on how to make it in scale. This has been especially difficult in Vietnam due to the lack of engineers able to work on AirPods 3 and other new devices.

This is the precise problem that I pointed out for India as well! Vietnam is perhaps several years ahead in tackling the problem.

Sharing the Pie: Inventory Risk.

Finally, it is worth noticing that just moving to a new production location does not eliminate disruption risk, as the suppliers and the production network continue to exist in China. So, how to overcome disruption risk? The sad truth is that global pandemics are only more likely, not less.

One way to solve disruption risk is to bear risk through additional inventory readily available. For instance, to guard against further supply chain disruptions, Apple had asked suppliers outside of the lockdown-affected areas to help build up a couple of months’ worth of component supplies for all their product lines — iPhones, iPads, AirPods, and MacBooks — to ensure supply continuity.

To be sure, holding inventory for your buyers and clients is a time-honored onerous task. Every shopkeeper knows that.

By asking the suppliers to hold two months of inventory, Apple is shifting the inventory risk to the supplier. There is a possibility that the demand might collapse for some of the products. The domestic US demand (where most of the revenues for Apple devices come from) is tapering — due to concerns about inflation, wage stagnation, political uncertainty, and plain old, commoditization of the products.

It is great for large firms that are able to essentially shift their risk. If you are a smaller firm down the tier in South East Asia, with barely any market power, you just “share the pain”, get ready to work out, and get more efficient.

Hobson’s Choice, really.

Do subscribe.

Turns out, it is nearly impossible to accurately measure a coastline.

https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/environment/a19068718/why-its-impossible-to-accurately-measure-a-coastline/